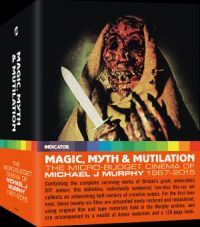

Of Magic, Myth, & Mutilation- The Films Of Michael J Murphy [2023-12-05]Between the late 1960s and mid 2010’s UK Portsmouth-based filmmaker Michael J Murphy helmed thirty one micro low-budget productions- these moved through genres such as costume drama, fantasy, horror, and Sci-fi. His work had largely fallen under the wider cult cinema radar - with only really his 1982 slasher Invitation to Hell being known- mainly due to its addition to the Video Nasty list. Early on this year saw the release of Magic, Myth, & Mutilation - A ten Blu-Ray set from Powerhouse - taking in twenty-nine of Mr Murphy’s feature-length films, a large selection of elements of uncompleted/ short films, a new three-part documentary, commentary tracks, and much more. Sam Dunn from Powerhouse- who put together & oversaw this huge release- was kind enough to give us an email interview regarding this truly epic & definitive boxset looking at the film work of this lesser-known, but highly prolific British genre filmmaker. M[m]: Michael J Murphy stands as one of the lesser-known genre directors. When did you first become aware of his work?, what was your first personal experience with his work?, and do think there are overarching themes/ elements running throughout all of his films?

Sam: I actually came quite late to the party, so to speak, having been too young to catch original VHS editions of Murphy’s work. It was really Darrell Buxton’s essay in Creeping Flesh Volume 1, I think, that sparked my interest, and which resulted in my seeking out copies from collectors and buying whatever DVDs I could find (such as the Thai edition of Death Run, as well as the later Sarcophilous Films discs of Invitation to Hell / The Last Night and Skare, of course). At that stage, it was hard to get a handle on Murphy’s work as a whole, but the welcome opportunity to see much more of his output came when the dedicated YouTube channel was put together.

M[m]: One of the few films Mr Murphy more notable films was his 1982 slasher Invitation to Hell, which I’m sure landed up on the video nasty list. Are you aware of what he personally thought about this film, and how would you compare it to the rest of the output featured in the box set?

Sam: I never knew Murphy, so can’t say what he thought of the film. He did, however, record an affectionate audio commentary for the Sarcophilous Films release, which we have also included on our release, that suggests he was proud of it.

In some ways, Invitation to Hell is a quintessential Murphy film, and is – in terms of its style, execution and ambition, at least – very much in keeping with his other work. However, its specific themes (of black magic and devil worship) are common to only a handful of his other films (such as Moonchild and The Rite of Spring). So, while it’s likely to be the starting point for many viewers as they find their way into and through the set, it’s important to say that, although Murphy is interested in the dark side of humanity (greed, selfishness, the capacity for destruction), not all of his films would be categorised as horror in the same way that Invitation to Hell is.

M[m]: And after the notoriety of Invitation to Hell- did he want to continue down the slasher path?

Sam: Looking at Murphy’s career, it’s evident from the outset that he is not interested in a single genre, but rather in exploring, even subverting, a range of genres. Broadly speaking, his work can be broken into a number of categories – thriller (Secrets, Road to Nowhere), murder mystery/whodunnit (Death in the Family, Torment, Roxi), horror (The Last Night, Skare, ZK3), rural/folk-horror (Invitation to Hell, The Rite of Spring), fantasy/adventure (Atlantis, Avalon), post-apocalyptic (Death Run), romance (Stay, the various Tristan adaptations), as well as what might be termed “self-reflexive” films (the primary examples of which are the notorious Bloodstream and his swansong The Return of Alan Strange). However, it should really be said that Murphy has his own take on all of these genres, and that his films are, first and foremost, imbued with a singular vision which creates an unmistakeable through line.

M[m]: Murphy’s filmography dates back to 1966 and finishes in 2016. This is a fair lengthy run- do you see his work as having set periods? And if so what are these?

Sam:There are a number of distinct periods, most obviously defined by the presence of various actor-collaborators. From the mid-seventies to the early-eighties, the films are mostly made on location (on Greek islands such as Santorini), are either two-handers or have a limited cast of characters, and mainly feature Caroline MacDowell, Carol Aston, Russell Hall, and Tim Morris in key roles. From 1982, Caroline MacDowell continues to be a major collaborator (and continues to be so right through to the early 1990s), but is now regularly joined by Steve Longhurst and Patrick Olliver. Bob Bartlett and Debbi Stevens take significant roles for a handful of films in the late-eighties, where they are ably supported by MacDowell, Longhurst and Olliver. By this time, June Bunday and Phil Lyndon have regular roles, too. And, by 1989, Olliver and Lyndon are regularly taking lead roles, as is Judith Holding. From this time on, Holding, Lyndon, Olliver, and Bunday will continue to appear in Murphy’s films, right up to and including The Return of Alan Strange.

Interestingly, after having set his films mostly on British soil since 1982 (the exception being Atlantis, although even that finds its way to London at one stage), the shift from 16mm filmmaking (after the devastating loss of the original Skare footage) to digital video also sees Murphy return to the Greek locations of his 1970s productions. It’s almost as if he experiences a kind of “re-birth” and consciously/nostalgically revisits the locations (as well as some of the themes, especially in Roxi) of his early works, thereby creating a sort of bookend to his career.

M[m]: Mr Murphy came from the Portsmouth area, and as I’m someone who lives a short distance from the city. Do you think his location made any impact on his output?

Sam: There’s not much I can offer by way of thoughts and reflections on the location as such, as it’s not an area I’m familiar with, but the filmmaking community which Murphy was a part of, along with his many and loyal friends and collaborators, was obviously hugely important to him, and continues to be to those who worked with him and who held him in such high regard. Without such people – including, but not limited to, Mike Reed and Phil Lyndon – and the efforts they went to in order to preserve and protect Murphy’s legacy, we wouldn’t have had the opportunity to put this hugely important collection together.

M[m]: His output shifted through different genres- was this a personal choice or market forces at the time?

Sam: Murphy was his own man, with his own interests and passions. While I think it’s fair to say that he was inevitably motivated to some degree by the need to sell his work, that need was almost exclusively driven by a desire to get the funds he needed to make his next film, rather than to become successful in any conventional sense of the word.

A great example of the way in which Murphy did not operate commercially, though, is 1985’s Bloodstream. While that film was made in response to the so-called “video nasties” scare, and on the face of it seems to be riding that wave, it is actually doing something entirely different. It is, not to put too fine a point on it, a sort of “loath letter” to the kind of fly-by-night opportunists who populated the video industry at the time, and who cared nothing for the films or filmmakers with whom they worked, but who rather only wanted to make a quick buck at the expense of the talent they exploited. Having made the film, though. Murphy promptly decided not to have it distributed (he being too gentle to make such a hate-fuelled, violent public statement), thereby foregoing what could have potentially been one of the most lucrative commercial opportunities he ever had.

M[m]: I believe you are putting all the films in the boxset through BBFC. Are they all having their first-time certification with the board, and have you come against any issues with the board regarding certain films? And will any of them have to be cut?

Sam: We had to submit all of the films to the BBFC and it cost us a small fortune. For a long time, we considered making the box set a US-only release so as to avoid the prohibitive and, frankly, crippling costs, but in the end decided that, because Murphy was a uniquely British filmmaker, we were duty-bound to release and honour his work in Britain.

M[m]: The Myth, Magic and Mutilation boxset stands as the single largest release Powerhouse has released to date. Please could you discuss some of the issues you faced producing & get ready the boxset for release?

Sam: Haha. Where do I start?! We faced challenges at each and every twist and turn. Delays occurred at every stage. And unforeseen surprises lurked around every corner. The unique nature of the project meant that there was really no precedent (either in our own catalogue, or indeed in anyone else’s), so, although we planned what we could, and set deadlines for delivery of the various assets and parts, the reality was that, until such time as we had those assets in-hand, and we knew exactly what we were dealing with, we really had no idea what we were actually up against (whether that’s from the perspective of image and/or sound quality, restoration problems, in/completeness, how the details in each essay and the filmographies tally with what’s onscreen, or indeed any other number of complex and inter-connecting issues). And, whilst we are obviously used to grappling with such problems on a monthly basis, and are, I’d venture to say, experts in problem-solving, the sheer scope and scale of the Murphy project made it almost impossible to plan to the degree we needed to, especially when the team was also, necessarily, attempting to manage a number of other projects at the same time.

One of the biggest challenges was putting the reconstructions of some of Murphy’s early films together. Using a mixture of 16mm footage (scanned in 2K from original, incomplete film elements), and sections of standard-definition material (captured by Murphy as he projected extracts from the films onto his wall during the 1980s before discarding them), we were able to assemble the material in order to present the most complete versions of each film possible. Whilst Michael Brooke’s technical skills, as both a picture editor and an audio “jigsaw expert” played a huge part in proceedings, it was Wayne Maginn’s (the set’s co-producer, and chief advisor on our Murphy project) deep knowledge of, and grounding in, the films which was of paramount importance.

But, even with the notes that Wayne had put together, it wasn’t until we were able to see how each reconstruction actually played that we were able to grapple with the fine-tuning. In some cases, the additional tweaks needed were few and far between, but in the case of Tristan & Iseult the only way to really see how the film would play was whilst actually undertaking the edit and watching and re-watching each iteration to find the natural rhythms and connections. This process of trial and error (which resulted in the assembly taking a number of days) is one of countless examples of how pre-production planning both played a vital part, but was also not able to help us at every twist and turn. And, try as we might, such instances – i.e., where we could only tackle the problem by seeing it first-hand – came up time and again.

At the end of the day, though, I’d prefer not to linger on these less-than-positive aspects, and instead to focus on the fact that we eventually, and I’d like to think successfully, managed to make it a reality. Despite the difficulties (and the excruciating BBFC costs), we are enormously proud of the end result, and can only hope that others will share our enthusiasm for Murphy’s extraordinary – and hitherto sorely neglected – films.

M[m]: As many of the films were barely released- what have you done regarding cover artwork for each title?

Sam: This was certainly a challenge, too. We needed to come up with a logical approach that could permeate every aspect of the set – slipcase, individual inlays, onscreen menus, disc labels, book, etc. – but, because Murphy worked in a variety of genres, and because original artwork for his films was either non-existent or varied wildly in its approach, we had no other option but to find a completely fresh way to create unity. In the end, we hit upon the idea of using the Powerhouse colours as a way to hold everything together. So, anyone who holds the set in their hands will therefore, hopefully, be able to see that each disc has been assigned its own colour (taken from the sequential colours in the “pH Indicator strip”), and that each of those colours is used across the set to distinguish the contents of each disc from that of the others. We rather like the end result.

M[m]: Are there any other cult/lesser-known directors' work you’d like to possibly release in a boxset form?

Sam: There are, but, for now at least, we’re taking a breath and getting back into the groove of preparing releases that are less than 34-hours long.

Big thanks to Sam for his time & efforts with the interview. The Magic, Myth, & Mutilation is still available in the UK- and can be ordered directly from Powerhouse website here

Picture credits: large front page pic still from The Last Night(1983), main menu pic Michael J Murphy, first in interview pic Michael J Murphy, still from Bloodstream(1985), box art, and still from Atlantis(1991). all are (c) Powerhouse Films- used with kind permission Roger Batty

|