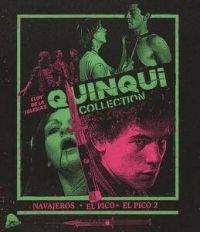

The notorious, gritty, and provocative Quinqui genre [2022-12-06]Late last year Severin released Eloy de la Iglesia’s Quinqui Collection- a two Blu-ray set bringing together three brutal and provocative Quinqui (delinquent films)- Avajeros (1980), El Pico (1983), and El Pico 2 (1984)- all directed by Basque writer/director Eloy de la Iglesia (video nasty The Cannibal Man). The Spanish Quinqui genre was popular between the late ’70s and mid 80’s- it focused on youth gangs, juvenile crime, and inner-city poverty- with the films featuring liberal (often real) drug use, violence, and sexual content. The pictures often starred non-professional actors picked off the street with a real criminal background. After being intrigued and taken by the set films and its extras- I reached out to Dr Tom Whittaker for an interview- he contributed to the excellent documentary on the set Blood in The Streets: The Quinqui Film Phenomenon. He’s an Associate Professor in Film and Spanish cultural studies at Warwick University, and also wrote the first English book on the genre The Spanish Quinqui Film- Delinquency, Sound, Sensation. The below email interview found us discussing the genre in general, as well as how music & sound is an important part of the genre's makeup. M[m]: What was your first introduction to the Quinqui genre, and is there any one picture that got you hooked on the films?

Tom The first one I saw was Deprisa, deprisa, by Carlos Saura on an old VHS. I was instantly struck by the naturalism of the performances – and the incredible soundtrack of flamenco, rumbas and disco!

M[m]: What do you see as the hallmarks/ elements of a great quinqui film?

Tom Some quinqui films are better than others, but they generally share a similar set of conventions. Firstly, the casting of non-professional actors in the roles of the delinquents. Sometimes real-life delinquents even ended up playing versions of themselves, such as José Antonio Valdelomar in Deprisa, deprisa or Ángel Fernández Franco 'El Torete' in Perros callejeros. Another key convention was that the films are focalised from the point-of-view of the delinquents, and not the police – this meant that the audiences were always rooting for the delinquent anti-hero. Quinqui films are transgressive, exciting – and fun! Finally, the soundtrack was very important: a great quinqui film was able to reflect what many teenagers in the cities were listening to at the time (gypsy rumba bands such as Los Chunguitos, Los Chichos and Bordón 4).

M[m]: I first came aware of you and your work on the genre with Severin’s release Eloy de la Iglesia’s Quinqui Collection, where you are one the key contributors on the forty-four-minute documentary The Streets: The Quinqui Film Phenomenon. Please tell us a little about how you got involved with this project?

Tom I was asked by the film distributor Severin Films to be involved for their international release of de la Iglesia's blu ray collection, where three of his films are available for the first time with English subtitles.

M[m]: after you were involved in the Eloy de la Iglesia Severin set, which features three of the director's films in the genre. What other films in the genre would you like to see getting blu ray reissues?

Tom I'd particularly love to see Deprisa, deprisa, Maravillas and Barcelona Sur get blu ray releases.

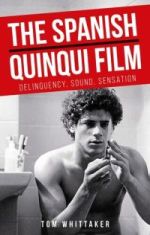

M[m]: one of your key contributions to your assessment of quinqui film is your wonderful 2020 book The Spanish Quinqui Film- Delinquency, Sound, Sensation. Please discuss how this came about, and how long did it take to write the book?

Tom Oh, I'm a bit embarrassed to admit that it took far longer than it should!. I started doing the preliminary research all the way back in 2012, and then started writing it in intermittent bursts from 2015 onwards. The writing part probably took 3 years in total.

M[m]: Through The Spanish Quinqui Film- Delinquency, Sound, Sensation appears on an academic publisher, it’s largely void of stuffiness and pretension connected with these types of books. How important was it to you to make it an approachable book- that would appeal to both academics, and wider film fans?

Tom Thanks - that's very nice to hear! Yes, I tried to make it accessible to a broader readership. I wanted my undergraduate students to be able to read all of it, but also professional academics and fans (although I do realise that the price is prohibitive for many...). I also wanted the technical analyses of the films to be racy and compelling – just like the films themselves.

M[m]: One of the most surprising things about the quinqui genre, is how popular it was in its native Spain in the 70s and 80s- why do you think this was?

Tom These films powerfully captured a country that was in the process of great change. They were produced as Spain was transitioning from the Franco dictatorship (1939-1975) to democracy, and was a period of great hope but also one of great uncertainty and fear. The delinquent stars in these films captured the rebelliousness and anti-authoritarianism of the time, but they also responded to several of the moral panics about crime which circulated in the Spanish press. Also, most forms of censorship were finally lifted in 1977, and this made quinqui cinema possible. All of a sudden, Spaniards could see films which depicted corrupt and violent cops, drug taking and casual sex – representations which were mostly impossible during the Franco years. There was also a baby boom in Spain in the 1960s, and as such, a new youthful generation were coming of age during these years. These films appealed to these teenage audiences, particularly ones living in the working-class suburbs of large cities such as Barcelona, Madrid and Seville.

M[m]: In your book, you tie in both sound and music as a key element in the quinqui genre- could you please discuss this a bit?

Tom The soundtracks were crucial because cine quinqui vividly reflected the auditory experience of marginality during this time. The songs that marginal audiences were listening to (by the groups mentioned above) at the time were incorporated into the soundtracks, and often used as a way of marketing the films. Soundtrack albums were also important. Another key component was the voice and vocal performance. The films were radical in the way they depicted how young marginal people actually spoke: you could hear the latest slang and swear words in these films.

The sounds of car engines, sirens and police chases were also important sonic motifs.

M[m]: I know the quinqui films still influence Spanish culture to a certain extent- but do you still think there are films still being made in the genre today, or can you see the genre's influence in other modern Spanish films?

Tom Carlos Salado's Criando ratas/Raising Rats (2016) can be seen as a neo-quinqui film, in the way it returns to the low production values, location shooting and non-professional actors of the original quinqui films, and is set in the contemporary moment. More recently, Las leyes de la frontera/Outlaws (Daniel Monzón, 2021) is what I would call more of a 'retro' quinqui film, in that it is set during the late 1970s and provides more of a self-conscious pastiche of the style.

M[m]: What are you working on at the present, and are there any new books planned/ in the pipeline?

Tom I am currently working on a range of projects: one focuses on soundscapes in Spanish history and culture from the 1950s to the present day. Another is looking at a broader history of crime films and thrillers in Spanish film. Finally, I am planning to write a new book on the Chilean director Pablo Larraín.

A big thanks to Tom for his time and effort with the interview. Eloy de la Iglesia’s Quinqui Collection is still available direct from Severin, and his book The Spanish Quinqui Film- Delinquency, Sound, Sensation is still available from Manchester University Press here. Roger Batty

|