Myths Behind The Maps [2012-06-01]-An Interview with The Psychogeographical Commission- Psychogeography, coined by the French Situationist Guy Debord in the mid-Fifties, questioned the ways in which places affect people, and particularly highlighted the negative consequences of urban architecture’s focus on function over form, providing a clear division between work and play for its inhabitants as they routinely experience the expected, their inquisitive senses dampened. More recently, aspects of psychogeography have been explored in modern literature, the most popular of which have included Ian Sinclair’s secret histories of London and Will Self’s regular provocative postcards for The Independent newspaper. But, despite music’s lifelong relationship to the environment, from the strategically sedatory effect of Eno’s Music for Airports to Annea Lockwood’s sound maps of rivers, overt aural expositions of psychogeographical secrets remain largely the preserve of audioguides aimed at tourists. The Psychogeographical Commission, formed in 2008 by Stuart Silver (S.:) and Andy Charlton (AKA Hokano), seeks to fill this gap between form and function by creating music that attempts to reconnect urban listeners with a sense of mystery, or to simply inspire curiosity, about where they live and work. Their first album, released in 2009, named after the Roman mythological ‘spirit of place, Genius Loci, asked its audience to listen while interacting with a city, so their blend of eerie folk song, electronic vapours and treated field recordings can form an unusual soundtrack to familiar surroundings. Since then, they have produced three further releases: 2010’s Patient Zero tracks the psychological effects of post-Summer solstice blues as the Autumn nights draw in, Widdershins exposes an ancient ritual underlying the Glasgow subway system and this year’s Urban Psychetecture showcases choice cuts from the first two albums augmented by a selection of cover versions of songs from Coil to The Moody Blues, perhaps indicating their preferred musical environment. Both S.: and Hokano recently spoke with Musique Machine about the rich concepts underlying their music and the ‘alternative’ realities that inspire them.

m[m]:

The Psychogeographical Commission aims to help people who live in urban areas to re-evaluate their surroundings and to discover and appreciate local mythologies usually assumed to be the preserve of more rural settings (from an ancient God of Newcastle-upon-Tyne to the banishing ritual of the Glasgow Subway system). How do you both go about initially discovering such mythologies? Have you academic or professional experiences in areas such as architecture or urban planning that has given rise to this unusual and rare pursuit or is it self-taught?

H : Personally I’ve got no academic training of any sort, just have a real curiosity from a very early age. I always looked up at buildings and wondered about them. Once you look up past the shop fronts you can find an amazing array of architectural anomalies. One of my favourites in Newcastle is the vampire rabbit adjacent to St Nicholas’s Churchyard who sits above a doorway to what was the dormitory for the monks and priests working at St Nicholas’s, it was put there to scare off any demons that might attempt to attack the sleeping monks. It’s just a shame that most people never look up and see the wonderful and sometimes curious statues and stained glass windows that exist above eye level, they never wonder who made them and why those figures in particular. S.: It’s mainly understanding the stories hidden in plain site, it’s about walking down the same streets as usual but looking at it with different eyes. Mythologies are easy to find, they’re all around you every day, in the statues, street names, the buildings and street layouts. Once you start thinking about them they come and find you. There’s been quite an increase in local history websites and forums where you can find stories and memories that can really give you new perspective on a place, you also find other people interested in the particular bit that floats your boat, be it tunnels, architecture, life in social housing, local legends or whatever. It’s one of those fractal subjects that becomes more interesting the more you find out about it because it can make you question fundamental things. Once you realise that a commonly known historical fact can sometimes be traced back to an odd sentence in a dubious 15th century book that you can tell even on first glance is full of errors, you soon realise that a lot of history is little more than myth and guesswork, and that there are more credible stories which can explain the facts better.

m[m]:

So what lead you to choose music and sound as the stimulus with which to promote psychogeographical sensibilities? Are you, perhaps, relocating folk’s traditionally rural settings to apply to cities in the same way you focus on urban instead of rural mythologies?

H : In the way that people like sitting there listening to nature? Possibly... S.: It struck me as odd that Psychogeography seemed to be a purely literary thing, because as great as the writing is, there’s an inherent disconnect because you can’t read a book whilst taking in your surroundings. It gives you the concepts to take in, but you can’t experience it at the same time. We’ve tried to take the same concepts, and put them into a more portable form. With adding the field recordings and everyday noises we’re trying to approach ‘city noise’ as music. Music is a very emotionally charged medium, so we just thought it would be ideal for trying to portray a sense of place. H: Listening to your environment is something people rarely do these days. Human beings evolved over the centuries to be in tune with their surroundings, to take notice of the details, or else you didn’t survive. Since we organised into an urbanised environment most people spend their time trying to block it all out or having it blocked out for them with constant advertising chatter and the like. Some people occasionally like to look around but it’s quite rare that they’ll just sit there and listen to what’s around them.

m[m]:

Stuart, you’re a pagan, but one that accepts that people live in cities and, therefore, you’re prepared to adapt your beliefs to the urban environment. Is this a unique approach or is it part of a wider movement, perhaps?

S.: I suppose you could see it as part of a movement but only in the way that a religion should naturally evolve to cope with changes in society. Chaos magick really opened the options out in the late 70s and 80s when it put more store in creating your own gods and rituals, stealing the techniques that work for you from other ideologies and generally deconstructing other belief systems to see what makes them tick then letting you reconstruct a system that works for you. Everyone’s psychological makeup is different and has different anchor points. The world is changing constantly so why shouldn’t beliefs evolve to keep up?

To me Paganism is really individualistic; it allows a healthy externalisation of your personal psychology, which means it only has to be relevant to yourself. I have no problems with more traditional pagans because that’s up to them, if it makes sense to you: run with it. I live in a city so it ends up being a part of who I am and the way I look at things

m[m]:

You’ve mentioned before that you are both more creatively productive at “times of lunar significance” and I hear you’ve been investigating Lunar Temples around Glasgow. What is it about the moon that seems to exert such power, and is it automatically received or do you harness it in any specific way?

S.: : Creatively the Moon for me is a meditation point that allows me to shift my perception to the slightly different headspace I like to write in. It allows me to make all sorts of interesting linkages both musically and lyrically that I wouldn’t have made otherwise. Most of my writing gets done at night when it’s really quiet so it’s a constant companion and the different phases of the moon can put you in different moods. The times of significance are mainly about fixed points in the year, as they progress they pretty much tell you which part of the cycles you need to be thinking about, they remind you that the seasons still progress even in the heart of a city. Occasionally there are rituals involved, but I’m pretty good at achieving the required state without.

The Lunar Temples are an interesting one though. A network of Temples was postulated back in the 30’s, based on some pretty dubious archaeology and perceived alignments. But like I was saying before, it’s these little ideas that allow you to perceive a place differently. You start exploring it further and you find all manner of supporting evidence in place names, geography and local folklore. It’s another example of finding a mythology, you start seeing the place through different eyes and you start reengaging with the environment again.

m[m]:

My first encounter with your music was on last year’s Widdershins EP, a seemingly subtle treatment of your field recording of a journey on the Glasgow Subway system, which leads me to assume that presenting everyday city sounds was central to your strategy for reconnecting people with their urban environments. So, I was surprised to find that your preceding two albums, Genus Loci and Patient Zero, are formed mostly of songs accompanied by guitar and atmospheric synths, albeit with field recordings often further down the mix. Is the Widdershins EP a one-off or are you finding that the actual sounds of the city are coming more to the fore in your work?

H: On the albums we’ve tended to approach field recordings as instruments, nice background sounds that blur the boundaries between what’s recording and what’s street noise, whereas on Widdershins it was more the basis for the entire project. I think we’ll try to do more projects like Widdershins down the line if we can find a location that can provide a narrative and a noise to collaborate with. We’ve got some projects coming up that are more narrated mythology/history than anything else and we’ll be using field recordings quite extensively.

m[m]:

When putting field recordings into your songs do you find they mix with music effortlessly – perhaps in the same way pretty much any soundtrack will sync with video at certain points – or do they often require the instrumental parts to be altered? Do they ever dictate the instrumental parts perhaps?

S.: : The field recordings tend to be really easy to work with. I usually write the basics of a song then we put the field recording in, then we’ll add the rest of the layers over the top. With Widdershins it was a bit different, Andy worked from the field recording up, augmenting and colouring to reflect the land usage above and I added small collages in for each station so it was the Subway that dictated the sound and I filled the silence while the doors were open. H: Sometimes a certain ambience of a field recording can dramatically alter some of my electronics as I prefer to try and make the synthetic sounds as organic as possible so that they blend in sympathetically with field recording. We even had one person who commented that it wasn’t until his second listen to Widdershins that he actually noticed that there were any synths on it.

m[m]:

With location being so important to your music, are you ever tempted to be more prescriptive about where (and maybe when) your recordings are experienced?

H: I think it’s going to be a lot easier to take an audience with you on a site specific journey when playing live. We’ll probably try to play some obscure places if we get the chance, hopefully some might have their own inbuilt sounds for us to play along to as well as an interesting ambience. S.: : Some things need to be more site specific than others, ‘Genius Loci’ was an album we wrote trying to capture a spirit of London and we tried to use some field recordings to merge the music into a background, to blur the boundaries when listening to it on headphones whilst walking about the streets, it was more of a sort of wandering album. I’m currently putting together a narrative for a project in Edinburgh which narrates a walk down a specific street; it’s sort of like an alternative guided tour. The idea is to slightly disorientate using field recordings which is at odds with the live street noise and to use the architecture of the street to tell a story which isn’t actually there but is based on facts you can check.

m[m]:

I find the idea of musically accompanying the live sounds of a specific environment fascinating, whether as part of a live performance or pre-recorded as an alternative guided tour. What inspired you to head you down this path?

S.: : We’d used field recordings quite a bit before, there’s quite a long bus journey on the end of Genius Loci which finishes the album beautifully, but I was sat on the Glasgow Subway one night after a few pints and just loved the noise that it made. The journey between each stops were a different length, speed and volume and crescendoed in different places like different songs. It struck me that the Subway was a continuously playing instrumental album and I started to wonder if you could recognise the individual songs on the album or add other instruments in to augment it. I think that was the chrysalis of our Widdershins project and once we’d done that and it sounded so good it’s set us looking around for another similar noise source to collaborate with. H: One of the earliest inspirations for creating an environment within an environment would be going to see a performance by Big Road Breaker who had placed speakers all ‘round the venue with microphones in different areas and then all the feeds were mixed so as you walked ‘round the venue all the sounds you heard were from another part of the room thus creating a different reality depending on where you are standing. Also I loved what the Paris Situationists did creating a riot in Paris just with tape players, at a prearranged time they set off the recordings of screaming, shouting and gunfire, the result: chaos. Plus I have a mischievous side that likes to play with people and confuse them as to what is real and what is performance.

m[m]:

Your latest album, Urban Psychetecture, available for free from your Bandcamp page, collects choice cuts from the first two albums augmented by cover versions of a song apiece from Coil, Roxy Music, The Edgar Broughton Band, The Moody Blues and Chrome. Aside from their track titles alluding to the built environment, do they partially map your musical influences?

S.: : Yeah to some extent. It was the Coil cover that gave us the idea for the album though: I was lucky enough to have a chat with Sleazy (Peter Christopherson) when he played Glasgow in 2010, we talked about the ‘Musick to play in the dark’ era of Coil and ‘The Lost Rivers of London’ in particular. I told him that it would be the only song we’d even consider covering but I was too nervous about doing it justice. He was very lovely and just said “Just do it and see what happens”, we eventually got around to the project and were really happy with the result.

The Chrome song was a favourite of mine. I was listening to it one day and I could suddenly hear how we’d do it, by ripping out the beat and the monster bass line, it works scarily well as a sort of ambient song. H: I’ll hold my hands up, The Moody Blues cover is all my fault being a Moodies fan for years, though I’d be hard pushed to find a direct influence. As much as possible I won’t listen to any electronic music when writing just so there won’t be any bleed through, but with there being so much music out there, a comparison will always be found.

m[m]:

If you were to plan a second volume of cover versions what other choices might be floated?

H : Well an obvious choice would be the Petula Clarke song ‘Down Town’, hehe, just kidding, S .: would rather eat his own hands than do that. S.: : No, fine by me, as long as you don’t mind me giving it the full Shatner Treatment H : On a more serious note ‘Empire State Human’ by the Human League could be an idea or maybe ‘Walk on By’, by Dionne Warwick probably using the Stranglers’ version as a template. On the subject of the Stranglers, ‘Strange Little Girl’ could be interesting given the PsychComm treatment. S.: : I was just saying to Andy the other day Neil Diamond’s ‘Beautiful Noise’ is one we really missed out on. There’s a Living Colour song called ‘Type’ which we might have been able to slow down and soundscape and perhaps Hawkwind’s ‘High Rise’, though it’s a bit on the negative side about cities. I do like a bit of Hawkwind now and again.

m[m]:

You both worked together before in a band called Aftercare that also featured Rich Blackett who contributed to your Patient Zero album and also records for your label, Acrobiotic, as part of the mysterious The Nothing Machine – is this an indication of a network of sorts of like-minded artists?

H: Haha yes, you’ve discovered our secret underground network with plans for world domination. S.: : I’ve known Andy and Rich separately for quite a few years before we got musical and now a lot of our projects overlap. The Commission is really just Andy and I at the moment, but early on we came up with our Alphalude project. We’d occasionally come up with nice little dead end bits of songs that were too good to throw away so we decided to use them to link some of the songs on Patient Zero. We’d just seen ‘Alphaville: A Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution’ and came up with the idea of having 60 of these small tunelets as a nod to the sentient computer in the film that runs the City (Alpha 60), with the intention of eventually editing them all together into one long piece. It also means there was an easy framework to ask other people to contribute small bits. H: The Nothing Machine Project is a larger extension of that. There are eight technicians working on the Nothing Machine full time, the first Therapy Recording only contained the noises selected by three of the technicians, the second Therapy Recording will contain sounds selected by five Technicians, hopefully we will get the remaining three to put down their clipboards long enough to contribute on later recordings.

m[m]:

So, outside of The Psychogeographical Commission and The Nothing Machine are either of you involved in other musical projects?

H: I‘ve got my part-time solo project under the name Hokano. I released one album a few years back called Ointment of Civilisation and there were plans for a second album to be released through Thonar Records, however, this fell through. It may see a release one day, but work with PsychComm and Nothing Machine tends to take up most of my time. S.: : I don’t really have much time for anything extracurricular either. Most of my time in between projects is spent doing research for future projects or reading up on all manner of esoterica to try to weave it into a narrative somewhere. That said, I’ve been thinking recently of doing an occasional solo ‘Noise performance’ thing, just small scale for a laugh, but I’ll have to see if I can find the time to do it justice.

m[m]:

I heard you suffered from piracy with your first album – what happened and have you found any way to mitigate the risk of the same happening again with subsequent releases?

S.: We originally released Genius Loci on CDR in large Map Book format which sold out surprisingly quickly. It got some great reviews and a lot of interest from distributors who asked us to glass master it so they could sell it. We spent a couple of months slightly remixing it and mastering it properly then released it. Unfortunately within a week of us reissuing it, a rip of the CDR appeared across the major download sites on the web which meant sales really slowed and any distributors who were stocking the reissue were stuffed with their huge margins on top H: Yes, unfortunately Genius Loci was put on various torrent and upload sites, which was a good and a bad thing. The good being more people got to hear the music and spread the name, but the other side of that was we lost quite a few sales and distributors as they wound up sitting on albums they couldn’t sell. We’re probably still to break even on that one but we learnt our lesson. S.: Widdershins was a limited minicd release with lots of artwork because we just tried to make it special enough that people would want the artefact and not download a rip. The next album we’re probably going to have to bundle as much as we can into pre-sales, and then probably release digital downloads a few weeks after the physical goes out to delay the inevitable as long as possible. H: There isn’t really a way to mitigate the risk we just have to hope that people who buy the music appreciate it enough not to give it away for free.

m[m]:

While people used to record LPs to tape to cheaply circulate music around small circles of friends, gaining kudos for their tastes along the way, uploading and sharing other people’s work on torrent sites seems largely anonymous while making endless amounts of copies available to a global audience. Why do you think people create torrents of other people’s work?

S.: : Hard to say really, I’m sure there are some out there with the best intentions. They find a band they like and want to tell the world about it. It’s one of the reasons we wanted to release a free album, to reach more people who don’t have to pay to give us a try. The difference is they release everything and call it advertising with the problem being that there’s never an incentive to buy the music and we lose money making it, whereas with our free download, we’ve deliberately tried to do it in a way which retains some value so there is still a point to buying the albums, there’s more songs and concepts outlined in the artwork when you buy. H: It did succeed in promoting the name but killed the album as far as sales went. I personally think they’re trying to get one over on the major music corporations by giving away their products, but all this really accomplishes is that the corporations step up their lobbying for control of the internet and producing music loses all its value. That’s workable for the major labels who can take a hit on reduced sales of the new Madonna album because their margins are astronomical, but when it filters down to the smaller labels and bands such as us, endless sharing does jeopardise the production of new material.

m[m]:

You played live in Glasgow earlier this year – how did it go with translating studio-based material into a performance? Do you have plans for future live shows, and, if so, where would you most like to perform (however impractical)?

H: The Glasgow gig was great. Being part of the film festival we wrote a whole new piece, which was specifically written only to be played live, based around an edit of the film ‘Heartless’. We have some plans for future live performances but chances are they’ll either be special events or more conceptual happenings. There are plans to try and do the studio work live at some point but the logistics of putting together a full band are proving tricky. S.: : I originally saw Widdershins as a live piece to be played on the Glasgow Subway with the Train as third member of the band. We did look into it but even if we could have convinced SPTE [Strathclyde Passenger Transport Executive] to allow us to do it would have been massively expensive so we couldn’t do it. I’d really like to play some underground cavern or tunnels, would be great acoustically and very atmospheric. I suppose performing a ritual piece inside the Great Pyramid would be fantastic, or a deserted military bunker? Anywhere with narrative and noise. H: I’d love to gig in the Vatican City I visited the public bits of it a few years ago and the acoustics in some of the rooms there are amazing, other than that I have always wanted to play in Japan.

m[m]:

What can we expect in terms of releases or performances from you both in the near future?

S.: We’re currently working on a new PsychComm album all about the mythologies of Roundabouts and the esoteric order of Roundabout Engineers at the heart of the Transport Research Laboratory. There’s another project based around using a Cabbalistic interpretation of the layout of New Town area of Edinburgh to explain chunks of Scottish social, political and religious history whilst walking down George Street, and I’ve also started researching for a multifaceted Glasgow project but that one will be a while off. H : And there’s helping out the Nothing Machine Technicians on their next Therapy Recording as well. There’ll probably be at least one more gig this year and we’re already thinking up ideas for next year, just nothing fully confirmed yet.

m[m]:

What has made you laugh recently?

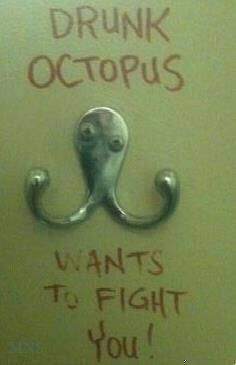

H: Rediscovering the film Harold and Maude and finding it’s still as funny as the first time I saw it S.: : I run our Facebook Page (www.facebook.com/psychgeographical) and I post all manner of bizarre signage, strange juxtapositions and photos which have unintended double meanings. Think my favourite in the last while have been the fighty Octopus,

It demonstrates the kind of alternate reality most of our concepts work in. -- Many thanks go to Stuart and Andy for taking the time to talk to us.

For further information visit their website: http://www.psychetecture.com/

Get your free download of Urban Psychetecture from psychcomm.bandcamp.com/album/urban-psychetecture Band photography: Alex Woodward at Crimson Glow Photography (http://www.crimsonglow.co.uk/)

Russell Cuzner

|